National Park Service

- In 1991, Donald Trump filed paperwork to slice up Mar-a-Lago's grounds and build eight mansions.

- Insider spoke to the preservationists and Palm Beach officials who opposed his plan.

- "Crisis at Mar-a-Lago," read a memo circulated among Washington preservationists.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

Six years after Donald Trump swept into Palm Beach, Florida, to buy the sprawling 1920s mansion known as Mar-a-Lago, he filed paperwork to slice up its grounds, build eight huge houses, and sell them for a tidy profit.

It was early 1991, a few months before Trump would file for bankruptcy for the first time with the Trump Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey. He was attempting to restructure the casino's debt weighted down by millions in junk bonds.

Mar-a-Lago was costing him more than $3 million in taxes and upkeep each year but not producing any income, a town official told the Palm Beach Daily News that year. Trump was looking for a way to make money from the property.

"When he had all these problems with bankruptcies, this was the one thing he had of value, basically," Laurence Leamer, the author of "Mar-a-Lago: Inside the Gates of Power at Donald Trump's Presidential Palace," told Insider via phone last month.

He added, "What was he going to do with it?"

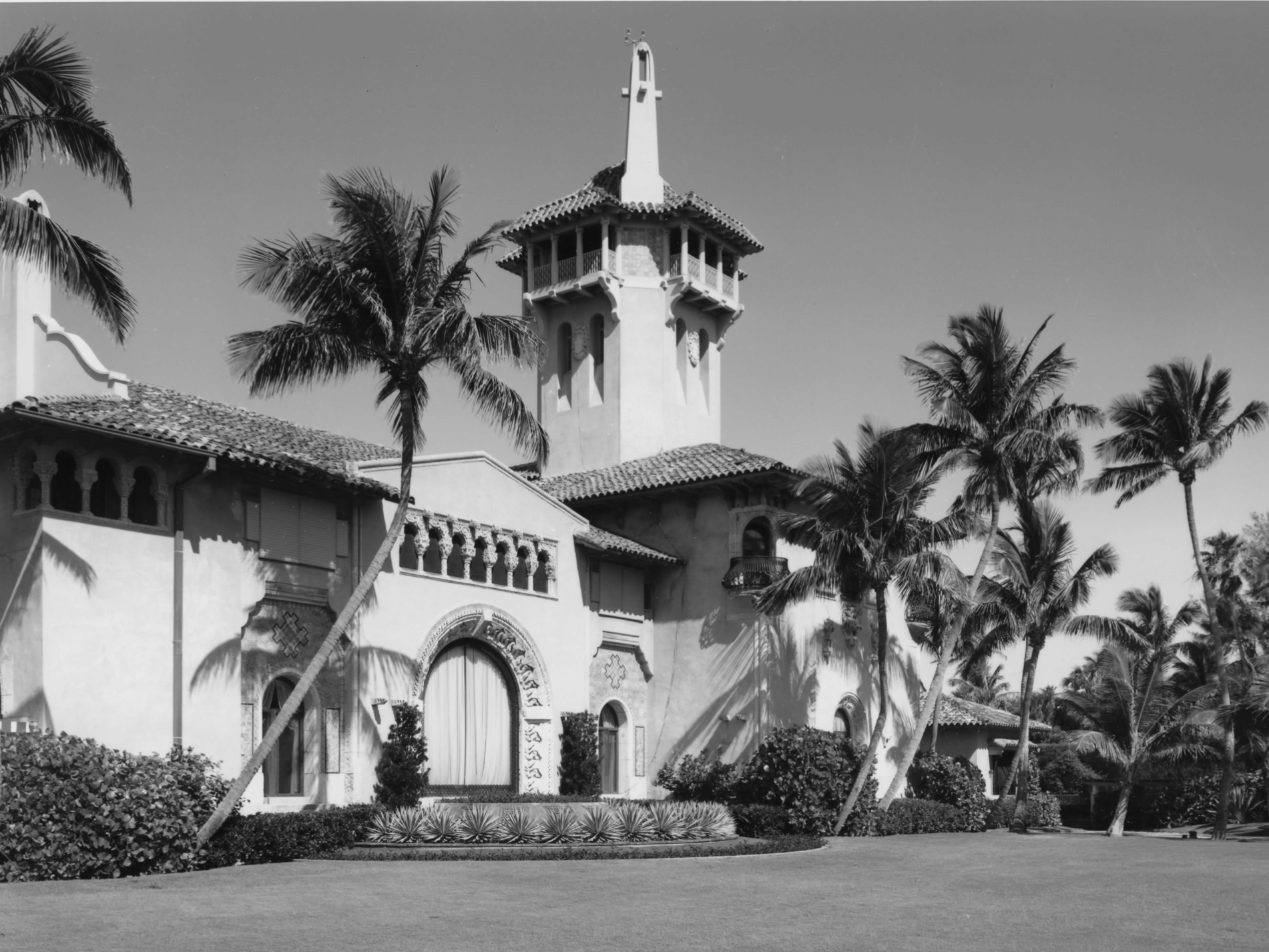

At the time, Mar-a-Lago was as beautiful as it is today. The centerpiece was a 62,000-square-foot structure, with a 75-foot tower, and pink-glazed tiles throughout. Builders had imported three boatloads of Italian stone for its exterior walls. The property cut across a thin island along Florida's Atlantic coast. Trump has since built a massive ballroom, complete with $7 million in gold trim, but little else has changed.

Trump's idea was to subdivide the 17 acres surrounding the mansion, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. He didn't plan to sell the mansion, just the grounds around it, according to public records.

But after months of scuffles with planning officials, locals, and national preservationists, Trump's plans to alter the property were denied.

He gave an interview to The Washington Post in August of that year, acknowledging the preservationists' role in stopping him. He told the paper, "If anyone else but Donald Trump owned it, they would approve it."

It would be a few years until Trump decided to turn Mar-a-Lago into a private club, with lucrative membership fees that would eventually climb to $200,000. While he was in the White House, the resort brought in a total of $93.5 million, according to annual disclosures filed with the Office of Government Ethics. But its future as a Trump flagship property wasn't always set in stone.

Tom Brenner/Reuters

To learn more about Trump's early days at Mar-a-Lago, Insider examined federal and local records, including hundreds of pages of Palm Beach documents from a Freedom of Information Act request. We sought out Palm Beach meeting transcripts, media reports, and financial filings.

Insider spoke to preservationists and Palm Beach officials who were involved with stopping Trump from subdividing Mar-a-Lago 30 years ago.

They said Trump was seen as an outsider - an interloper from New York - making waves in a tightly knit and wealthy community. They said he wasn't willing to play by the sometimes unspoken rules of Palm Beach real estate, where everyone knew one another, and where historic preservation was paramount.

"And he would not think a thing of National Historic Landmark status, except that it might confer some prestige to him," said Tersh Boasberg, a preservation lawyer in Washington who organized a group of national preservationists against Trump.

The Trump Organization and The Office of Donald J. Trump did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Tim Frank, an architect who was the special-projects coordinator for the Palm Beach Landmarks Preservation Commission during the proceedings in 1991, said, "Let's face it, everybody that sits on my commission probably - this is just a statement - probably had more money than Trump anyway, so they weren't intimidated by the guy."

Frank added, "I mean, he's nouveau riche."

A winter retreat

After the cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post's death in 1973, Mar-a-Lago was gifted to the US government. Nine years later, officials handed it back to Post's charity, the Marjorie Merriweather Post Foundation. Officials no longer wanted to pay for the upkeep, according to government documents.

Over the next few years, prospective buyers came and went. A sale to two Boca Raton developers for $13.5 million fell through, The Wall Street Journal reported in 1984.

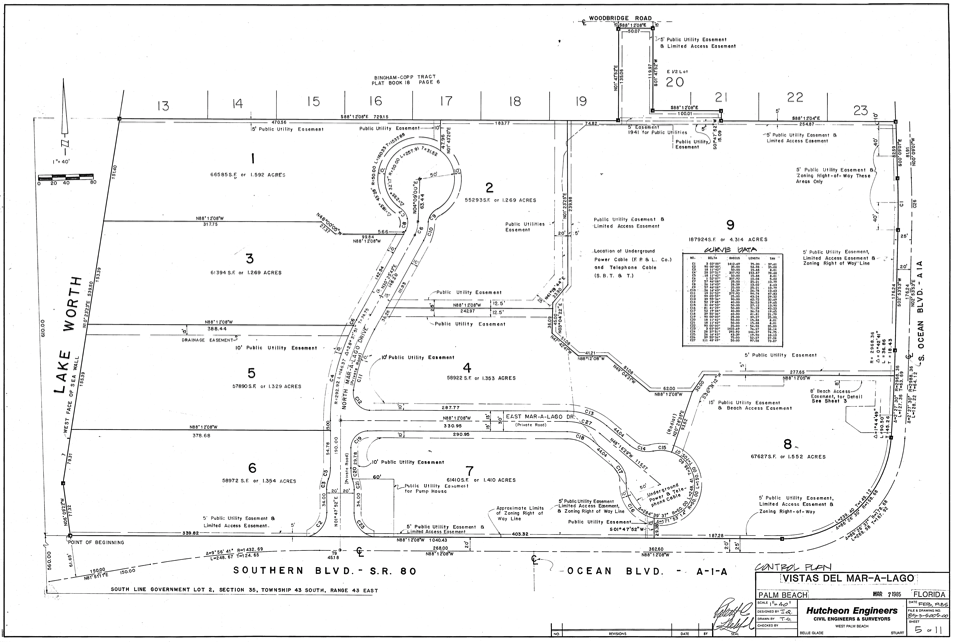

The following year, the Palm Beach mayor and town council wrote a letter to the National Park Service asking to subdivide the property, making it easier to sell. A buyer made a $12 million offer, but only if he could add eight or nine homes to the property, according to an NPS brief. But that deal fell through, too.

"The town agreed upon it - to subdivide it when somebody previously was going to buy it," Leamer said. "When Trump got it, he didn't get permission to do that."

Town of Palm Beach

The listing on the National Register was among the selling points. Cecil N. Mckithan, an NPS landmarks coordinator, summed up the property in 1981, saying: "Mar-A-Lago exemplifies the baronial way of life adopted by the affluent society of the 1920's during the land boom that opened Florida to winter resort development."

Mckithan would also include a description of the "whole property," which would prove crucial. The same had been done in an earlier designation of the property's historic status, signed by Stewart L. Udall, secretary of the interior, in 1969, according to NPS documents.

When Trump purchased the house, a representative said he planned to use it as a private residence, according to The Miami Herald, which ran a story about the deal on its front page in October 1985. The story, which labeled Trump a "flamboyant millionaire," quoted an anonymous source, who said, "He plans to maintain a low profile."

A United Press International story from January 1986 placed the sale price between $10 million and $15 million.

The Herald later reported that the actual selling price listed with Palm Beach authorities was just $5 million. But Trump also bought much of Mar-A-Lago's furnishings and a $2 million beachfront property in front of the existing property perhaps bringing the total price closer to the original range, the Herald reported.

In the National Historic Landmarks Program's hundreds of pages of Mar-a-Lago files, there's a yellowed newspaper clipping without a byline, date, or publication name. That story said: "Unlike previous developers, who planned to subdivide the land, Trump will keep the house intact as a winter retreat."

The planner and the architect

A few years later, Trump's subdivision plans arrived on Frank's desk. As was usually the case in Palm Beach, they were delivered by a close friend. This time it was the architect Eugene Lawrence, whom Trump had hired for the project.

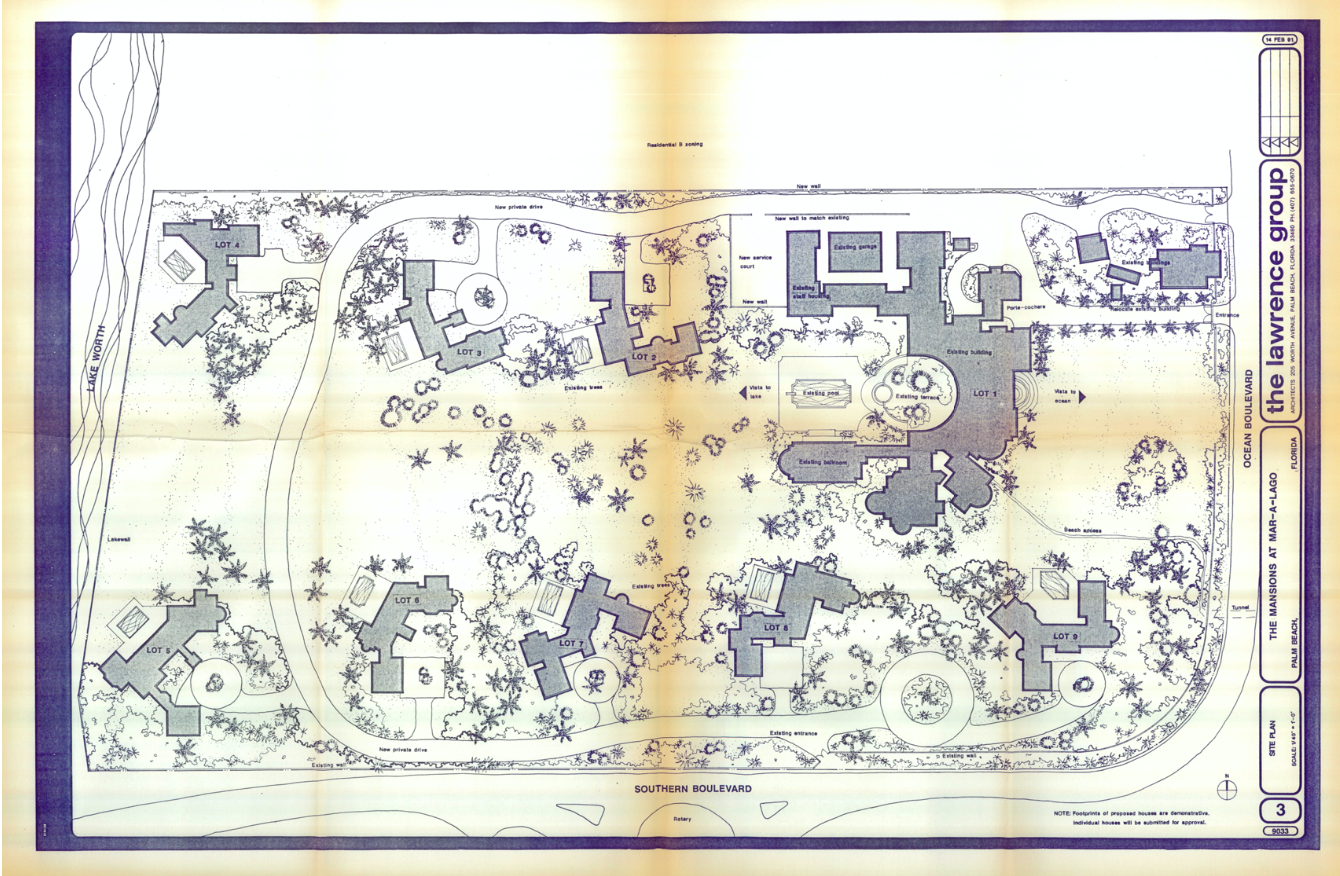

The plans called for the 17 acres surrounding the original mansion to be rezoned to add more houses. A perimeter road would be paved, and eight new homes would fan out around the existing Post mansion, according to drawings prepared by the Lawrence Group. Collectively, they'd be known as "The Mansions at Mar-a-Lago."

Homes similar to those in the proposal were selling for about $6 million apiece elsewhere, Lawrence told the Herald in February 1991. Using back-of-the-envelope math, Trump would bring in about $48 million when he sold the new homes, excluding the cost of building and marketing them.

"These are going to be major homes," Lawrence told Herald.

National Park Service

At the time, Donna Beinstein was a junior architect at Lawrence's firm, helping the senior architect draw the plans.

"I think that Trump came to him because he had been in Palm Beach for quite some time and knew a lot of the people in Palm Beach that we would be dealing with in the process," said Beinstein, who now works as an architect in Connecticut.

She said the proposed mansions were designed to be about 10,000 square feet apiece, much smaller than the 62,500-square-foot Mar-a-Lago.

Beinstein still has various versions of the Mansions at Mar-a-Lago. They showed a design in flux. Within a few months, the number of new homes shifted from eight to seven. And the perimeter road was moved away from the intercoastal waterway, to improve the view of the water and make room for the golf course.

Local preservationists signaled they had doubts about whether Trump's plans would be in keeping with the property's historic design.

In March 1991, Charles Millar Jr., a development planner with a Palm Beach law firm - Moyle, Flanigan, Katz, FitzGerald & Sheehan, P.A. - sent off a letter to the chief historian at the NPS in Washington. He enclosed the subdivision plans.

"Time is of the essence concerning this impending tragedy," Millar wrote in the letter, a copy of which ended up in the NPS archives.

It was one of several letters that reached federal preservation officials that spring. They all seemed to be seeking one thing. They wanted to put an end to Trump's project.

A feisty historic preservationist

In the days before a May 17, 1991, Palm Beach meeting to discuss Trump's plans, a short memo written by Boasberg began circulating in Washington.

"SUBJECT: Crisis at Mar-a-Lago," it said, adding: "Unless Trump's plan is nipped in the bud, the new subdivision (with its eight mansions, various outbuildings and new road) will irreparably damage the National Landmark."

Boasberg, the Washington lawyer, now 86, answered a phone call from Insider a few weeks ago by asking, "How did you find me?"

He'd been a driving force against Trump on the Mar-a-Lago project, after Barbara Hoffstot, an eminent preservationist, who'd lived part time in Palm Beach, asked for his help. The two met at a preservation event in Washington, and she'd enlisted him almost immediately.

"She was a stalwart. She was a very feisty historic preservationist. She did not want to see that property subdivided at all," Boasberg said.

He wrote the memo about the "Crisis" at Mar-a-Lago, sent it around to every preservationist he knew, and then flew down to Florida for a series of meetings on the subdivision. A who's who of Washington preservationists showed up at the meeting, according to a report in the Palm Beach Daily News the following morning.

National Park Service

Boasberg remembered the room was packed wall to wall. The Palm Beach Post quoted him the following morning: "There is tremendous concern in the country about what is going to happen to his national historic site."

Though Mar-a-Lago was listed on the National Register, giving it prestige, the actual decision about changes to the property would be made locally. Historic properties can be recognized at the federal level, but they're regulated by local laws.

At the same time, local groups in Palm Beach were rallying against Trump. Their leader was Polly Anne Earl, the executive director of the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach.

L. Frank Chopin, the legal counsel at Earl's foundation, began the meeting with a "scathing 40-minute argument," according to the report.

"This application cries out for deferral," Chopin said, according to the report.

That first meeting was contentious, according to reports the following day in Palm Beach. Trump did not attend. After both sides had their say, a decision was postponed, according to the minutes.

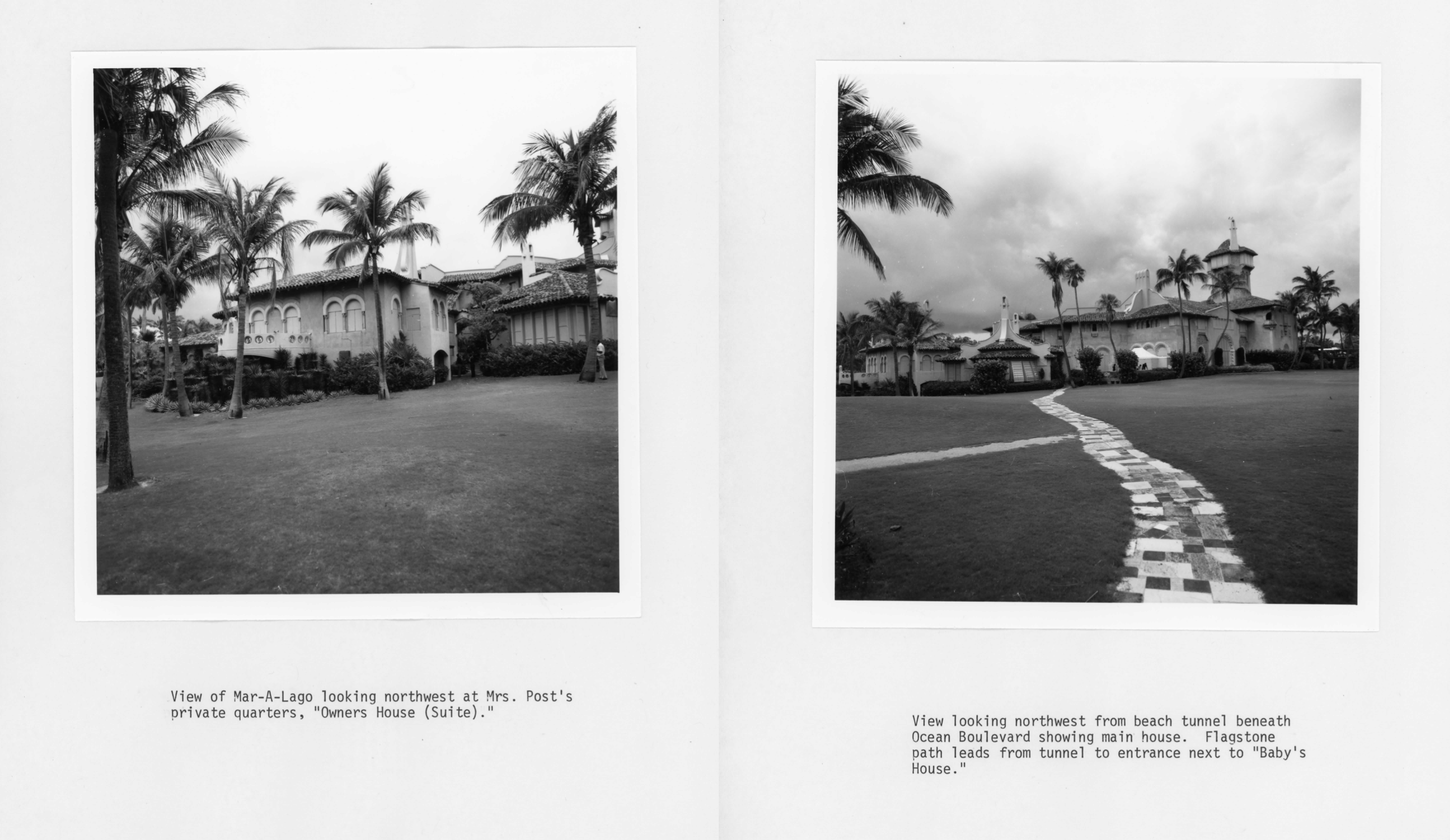

Boasberg said he went out to Mar-a-Lago with a group of preservationists, trying to get a sense of the scale of the proposed changes. He remembered pushing his nose up against a fence to get a better view. He didn't remember being allowed on the property.

"It might've needed a coat of paint or something, but, I mean, it wasn't run down," he said. "It was a spectacular property."

A 'deliberate fabrication'

By all accounts, Trump skipped most of the public meetings held in Palm Beach. His lawyers and designers were always present, and he was often mentioned by name. But he's not listed in the official minutes. And the people Insider spoke with didn't remember him being there.

"He wouldn't deign to come to something like that," Boasberg said.

To some - like Leamer, the author - the months Trump spent trying to subdivide the grounds would be seen as a "blip" in the long fabled history of Mar-a-Lago. But others involved in the back-and-forth with Trump told Insider that they now viewed the ordeal as a testing ground for Trump's later battles against officials whom he viewed as pencil-pushing bureaucrats, including members of the "swamp" in Washington.

News clippings from the time show that Trump attempted to influence the town's decision and sway public discussion by speaking to the press. It was a skill he was still honing in those days.

After the first meeting, a photographer and a reporter from the Palm Beach Daily News visited Mar-a-Lago for an interview.

Trump told them he was seriously considering selling the property to the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, the leader of the Unification Church. Moon's followers, called "Moonies," a term the church dislikes, were known for extensive outreach into the community.

Reuters Pictures Archive

The paper quoted someone close to Trump saying, "If [the town] thinks they don't like a subdivision of Mar-a-Lago, what are they going to do when a thousand Moonies descend on Palm Beach every weekend?"

The comments echoed around the country, with blurbs in the The Seattle Times, The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and elsewhere.

When a Knight Ridder reporter reached out to the church for confirmation in 1991, a spokesperson called the deal a "deliberate fabrication," and asked for a personal apology from Trump.

A church official got Frank on the phone the following week, clarifying that the church had never been interested in the property. The church's New York office sent out a press release calling Trump's comments a "blatant recent example of outright racism and bigotry."

Last week, Sungmi Orr, a church spokesperson, confirmed that the the church "never intended to buy the property nor had any interest in it."

"No apology was received nor is required from Mr. Trump," Orr said in an email.

A monthslong struggle

A second meeting was scheduled a few months later. The pattern repeated itself. In the days before a June 21, 1991 meeting, a flyer began circulating.

"RED ALERT," it said in a large font.

It called for all residents of the town to flood Town Council Chambers to push for an end to Trump's plan.

"The chance to ensure a careful, sensitive, aesthetic treatment of Mar-a-Lago, house and grounds, will only occur once," said the flyer, issued by the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach.

Again, Boasberg, Earl, and a host of other preservationists were on hand to give testimony against Trump's plans.

Over the course of the next few meetings - the discussion was postponed a few times - the people opposed to Trump's plans said repeatedly that the grounds were just as important as the mansion. They were echoing the language used in the National Historic Register forms filed out by Mckithan a decade earlier.

Carlos Barria/Reuters

At one meeting, members of the Garden Club of Palm Beach noted that "every blade of grass" had been included in the property's historic designation. Removing trees or other green elements might change the ecosystem, they said.

"This made us think of mosquitoes," one Garden Club member said when the floor was opened to comments. "So, it seems that in addition to mansions at Mar-a-Lago, we're going to have mosquitoes at Mar-a-Lago."

That the grounds were so important turned out to be among the final nails in the coffin for Trump's plans, Boasberg recalled. He said it was lucky they'd been detailed in the National Historic Register documents filled out by Mckithan a decade earlier.

He recalled sitting in one of the meetings, listening to a parade of preservationists make the case for the importance of Mar-a-Lago's grounds, and knowing at that moment that Trump's plans wouldn't be approved.

But Frank remembered another detail that, he said, was perhaps more influential in leading to the commission denying Trump's plans.

Trump was asked to return with a historic preservation plan that showed how money raised from the sale of the subdivided property would maintain the central mansion in perpetuity, Frank said. Palm Beach officials needed to see that the money Trump made from the subdivision would keep the original mansion in good repair for years and decades to come.

The task fell to Lawrence, the architect and Frank's friend.

Lawrence went away to work on the plan. Weeks later, he came back with "a three-ring binder that was probably half an inch thick, and it was filled with crap," Frank recalled.

He added: "Actually, I've got to portray this accurately, because he's deceased and I don't want to distort this in any way, shape, or form. But Gene indicated to me that he essentially wasn't empowered to do that. My guess is Trump basically said, 'Throw something at them.'"

Lawrence had presented a plan that predicted a tax windfall to Palm Beach and the county. The homes would generate about $106,000 each year in new taxes, he said.

But that wasn't enough, Frank said. In the end, it was the Trump team's inability to present a business model that would keep the mansion in good condition that doomed the project, Frank said.

"The following month, based on my discussion with Gene and the fact that he didn't give us anything else, the Landmark Commission essentially officially rejected the plan," he said.

A team of consultants hired by the town had also concluded the plans would destroy the estate. On August 16, 1991, the commission unanimously voted to deny the plan.

Trump was quoted in the Palm Beach Daily Post the following day, saying he would appeal. He would eventually sue, but never get to subdivide the property.

"We came with a sensitive plan. We have the right to get a larger subdivision - 12, possibly 14, lots," he said.

A tribute to preservationists

But by June 1992, Earl and the other preservationists were confident enough that Trump's plans had been permanently squashed that she sent a congratulatory letter to a preservationist at the National Park Service.

"For eleven months the Preservation Foundation struggled to bring these issues into the debate on this issue," Earl wrote. "The fact that they were finally addressed is a tribute to your efforts and those of the national preservation community."

Joe Skipper/Reuters

In the hundreds of pages of NPS documents relating to Mar-a-Lago, Insider located only one with Trump's signature on it. In September 1993 he wrote a four-page letter asking for approval to build new walls, pave a parking lot, and put an end to air travel over the mansion.

The letter was mostly complimentary, but buried within it he argued that preservation groups "which have a legal obligation to protect landmark properties have so far failed to be responsible partners in the preservation of Mar-A-Lago."

Trump continued, "If this inequity is not questioned and corrected, over time it will have a chilling effect on the willingness of other individuals to voluntarily dedicate their resources to preservation."